A couple of days ago someone alerted me to a

book called

The Clear Line in Comics and Cinema, a Transmedial Approach, written by David Pinho Barros. They did this because it had a small section looking at

The Rainbow Orchid.

I have to say that these days I do not go looking for reviews of my work - positive or negative. Positive ones make me squirm and feel unworthy, and negative ones make me feel bad - neither is enjoyable (though I am very grateful for the positive ones).

The book looks really interesting, despite the fact I'm a little wary of the overanalysing of an author's works. But the intersection of clear line comics, a highly narrative form of storytelling, and parallel philosophies in film is quite fascinating (and one of the directors Barros looks at is Yasujiro Ozu, a favourite of mine).

cover for The Clear Line in Comics and Cinema, art by Joost Swarte

I am jumping the gun, I have not read it yet, though I do intend to. But I did screw up my courage and skim-read the section on The Rainbow Orchid, and here I saw a statement that I want to address as I do feel it misrepresents my motivations.

Firstly I should say I'm a great believer in the idea that once you've finished a work and it goes out into the world, it is no longer your possession. It belongs to whoever picks it up and reads it, and they can bring all their thoughts, beliefs, prejudices, biases and feelings to that work and interpret it however they want. They may not align with the author's, and they may read things into the story the author never intended or meant, and that has to be the way it is.

In chapter 3, 'The clear line after Tintin et les Picaros', Barros says: "I propose to look at two [authors] in particular: the French Olivier Marin and the British Garen Ewing. In both cases, their use of the clear line is mostly a consequence of a selling strategy, which, by proclaiming a graphic affiliation with the classic series, aims at attracting the nostalgic reader and, simultaneously, surprising him or her with contemporary representations of topics which were proscribed in the youth magazines of the likes of Tintin, such as highly eroticised renderings of the female body."

That last bit about the "female body" refers to Olivier's work more than mine, but I'm a little perturbed that isn't clear, especially as I made the decision not to sexualise any aspect of the characters or story in that book. And that idea is connected to the main point - that The Rainbow Orchid uses the clear line style as a 'selling strategy'.

This could not be further from the reality of the comic's origins. Back in the 1990s I was looking more seriously at working in comics. I had done a lot of fanzine work and felt my art was improving so I was getting a portfolio together and going to comics shows and meeting professional artists and editors.

Thanks to this I went through a process of realisation - I didn't think I actually wanted to get into professional comics after all. While I had enjoyed working with various writers, I knew the main thing I liked doing was creating and writing stories, and being the illustrator for someone else's vision did not fulfil that aspiration. And this wasn't a reaction to a lack of success, in fact it came about when I started to have some succes - having work accepted for Heartbreak Hotel, doing a full US superhero comic for Blue Comet Press, and particularly after having an enthusiastic response at a convention with a DC editor and an invitation to contact them for work on a new black and white imprint they were starting.

I never followed up on that last one because I was coming to the realisation that this was not what I wanted. I found drawing hard, I wasn't naturally talented and I wasn't fast (essential for comics) - but I did enjoy it, and I really loved the comics medium. After some soul-searching I decided to concentrate on a career as an illustrator and leave the comics as a spare-time pursuit, something I could just enjoy for my own gratification.

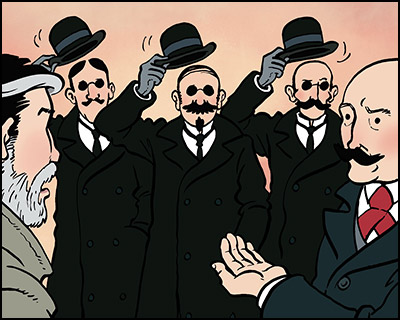

Mr Tardy, Mr Tardy and Mr Tardy, The Brambletye Box by Garen Ewing

What did I enjoy? Big fat escapist adventure stories! Also I wanted an antidote to all the gritty 'adult' comics that were everywhere at the time. My art was naturally cleaning up, particularly after adapting The Tempest I was appreciating simplicity, reduction and clarity. I'd had my first paying job, for a newspaper, and was able to complete my collection of Tintin books - the staple (along with Asterix) of my comic-reading childhood. More importantly I had just discovered Blake and Mortimer, and had bought my first Jacques Tardi book.

So, I'd decided. I would not work towards a career in mainstream comics but instead concentrate on working as a commercial illustrator, the comics would be purely for my own enjoyment, self-published for whatever small readership would gather in front of me.

Things changed when the internet arrived. I got on it in about 1998 and started putting The Rainbow Orchid up as part of my website in about 2005. Without much publicity (I was still treating it as a hobby) it started to gain traction anyway and largely thanks to some much larger web-comics coming across it and linking to it, the readership escalated.

It's another story, but this kind of exposure lead to an agent and eventual mainstream book publication and, of course, vast wealth (yeah, joking on that last one). I chased none of these things, they came to me, though I was very happy about it, of course.

That's an overly-long ramble to the statement that my use of the clear-line is the "consequence of a selling strategy". I do resent that idea, and it's explicitly because that makes it seem like the decision was rather a calculating scheme to elicit sales in the marketplace - the opposite of what actually happened.

I don't want to have a go at David Pinho Barros for his remark. Although I have talked about the origin of The Rainbow Orchid I can't expect him to seek out everything I've ever said. He does quote the following I wrote for my website many years ago (still there in my faq) ...

"I wanted to invoke the atmosphere I loved from European adventure albums such as Hergé's Tintin, Edgar P. Jacobs' Blake & Mortimer, Yves Chaland's Freddy Lombard, and Tardi's Adèle Blanc-Sec, to name just a few. Most British readers cite Tintin because not many other ligne claire comics have made it over from France and Belgium, but it is an entire school of comic strip storytelling with many creators working in the style, just like manga often has a certain look to it. The Rainbow Orchid has been compared stylistically to Floc'h's Trilogie Anglaise or Jacobs' La Marque Jaune. The better you know Tintin, the more apparent the differences, but I don't refute the similarities - it was a conscious decision."

... and I can certainly see how a 'conscious decision' to invoke the style of Hergé and Jacobs might be seen as a commercial choice, though actually it was merely one born out of enthusiasm for exploring the form for myself. I guess that's the bit missing - I wanted to invoke that atmosphere for myself.

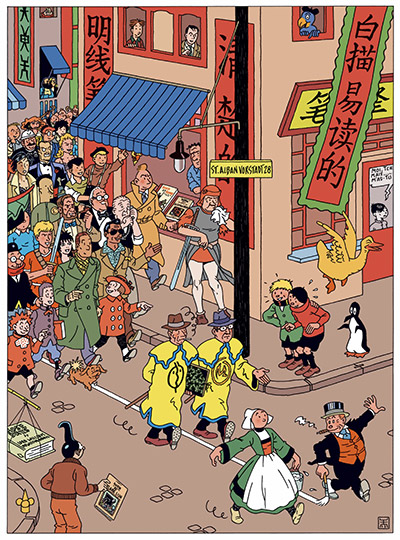

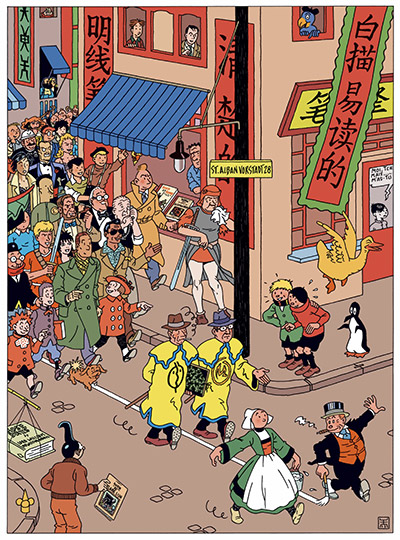

Art by Exem for the Cartoonmuseum Basel

There's nothing wrong with making an artistic decision in order to maximise revenue, but it does have the feeling of an accusation, and offers the idea that money, not art, is the driving force, something that is generally frowned upon. And not that I'm against making monery off my art - far from it - and I strongly dislike the conceit that 'true art' can only go hand-in-hand with poverty.

Since having the book out, and even being lucky enough to have it appear translated in the Franco-Belgian world that inspired it, I have seen the more commercial side of the ligne claire. It certainly has an aspect of marketability in Europe. In the UK my largest audience was children (although not explicitly a children's book), whereas in France, the Netherlands and Germany, the largest audience I saw was people like myself, older, mostly male, and nostalgist collectors (not exclusively, and also not a problem by any means!).

This is partially due to the publishers, smaller, boutique publishers who cater to that audience with reprints and classic series. With a much bigger publisher in the UK (Egmont) the readership was hugely varied, children, teens, adults, quite strong in both male and female readership.

I actually suspect the style I've chosen to work in has been a hindrance in my own country, as so many people are familiar with Tintin, and nothing else, that I can appear merely as a copycat or fan-artist. While I was making Orchid I purposefully didn't look at a Tintin book - for years - wanting to develop my own ligne claire style. Of course it's always going to be compared to Tintin, and fair enough.

Now I have returned to the point I was at twenty years ago - a new Julius Chancer book and I'm doing it for myself. I haven't signed with a publisher and don't strongly mind whether I do or not - it would be preferable, of course, but I'm happily prepared to self-publish. I'm more aware of the 'clear-line scene' now, and certainly I've changed since The Rainbow Orchid, the comics scene has vastly changed, so my comics have changed.

Anyway, that answers the point I wanted to address about my book's motivations! Whether it's a wise thing to do I'm not certain, but, especially as I get older, I see my creativity as part of my identity, and feel the record should be corrected, even if just here on my blog.

I hope I haven't misinterpreted Barros's writing, and I do look forward to reading his book, which looks fascinating. I'm enormously flattered he even chose The Rainbow Orchid for inclusion, it's a privilege to be part of it whether praise or criticism. You can download the book yourself from here.