|

|

|

|

|

|

Maiwand

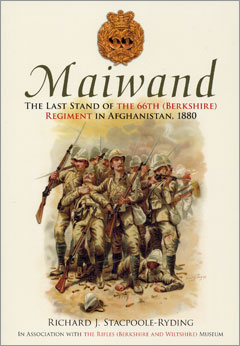

The Last Stand of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment in Afghanistan 1880 a new book by Richard J. Stacpoole-Ryding

In April 2007 I was delighted to be asked to join a group of Afghan War and Maiwand enthusiasts, co-ordinated by The Rifles (Berkshire and Wiltshire) Museum (aka The Wardrobe) to put a book together about the 66th Foot and their time in Afghanistan, leading up to the battle of Maiwand. The team included David Chilton, Martin McIntyre, Richard Stacpoole-Ryding (the author), Andy Chaloner, John Jordan, Ian Cull, John Chapman and myself. My contribution was in the form of helping with research and notes, drawing the maps and writing the introduction, which I reproduce here... Introduction to the book written by Garen Ewing After almost 130 years, British army boots are once again making their impression in the sands of Helmand Province in southern Afghanistan. However, the sound of gunfire is certainly no stranger to the mostly Pashtun tribespeople who live in the hot and dry river valley. In the twenty-first century it is the sound of the SA80 and Minimi Light Machine Gun, against the mortar rockets and the bark of the AK47 wielded by Taliban insurgents. But the last time the British fired their weapons in battle here, in the same dried out nullahs, and in the same 60-degree temperatures, it was the sound of Armstrong cannon versus Armstrong cannon, and the Martini Henry breech-loader and its bayonet versus the sharp crack of the jezail and the primitive but deadly Afghan 'Khyber' knife and tulwar sword. More than a century may separate these conflicts, but a thread can be traced back connecting the British in Afghanistan today with their forebears in the nineteenth century. As today, the British Government in 1878 wanted to stabilise Afghanistan in order to prevent danger to their own territories. To achieve this goal they used military intervention, not to rule themselves, but to make space for a homegrown government that would be sympathetic to British needs. The soldiers who worked for their shilling or rupee were of an international alliance back then too, though under somewhat different circumstances, it has to be said, as both coins bore the head of Empress Victoria. Shoulder to shoulder with the Berkshire Tommy, was the Baloch sepoy, the Muslim sowar, and the Hindu bugler. And on 27th July 1880, they all stood together, exposed on an open arid plain, while an army estimated at between 10,000 to 20,000 Afghan warriors and tribesmen advanced, firing their artillery pieces with such accuracy that a rumour quickly spread among the Anglo-Indian force that Russian commanders must be present (though it would take another one hundred years before Britain's 'Great Game' opponents took their big guns from Kushka and Kabul down to Kandahar). Along with Isandlwana in South Africa the previous year, the battle of Maiwand stands as a rare British disaster in a time when the pith helmet and redcoat (actually khaki in the case of Afghanistan) dominated the world. For the Afghans it became a source of national pride, embodied in the form of Malalai, the heroine of Maiwand, and Ayub Khan, the 'Afghan Bonnie Prince Charlie'. For the British it became a day of noble sacrifice, gallant heroism and an event to be overshadowed as soon as possible. As Rorke's Drift took the focus off Isandlwana, General Roberts' relieving march from Kabul to Kandahar, and his subsequent victory over Ayub Khan at Babi Wala, quickly became the stuff of Boys' Own legend, not to mention the fact that a special bronze star was awarded to its participants, much to the chagrin of some who had also worn out their boots on Afghanistan's stony plains, but were not among the 10,000 chosen for this glorious event. While Roberts' famous march is just about still remembered today, it is Maiwand that remains the most potent area of fascination for historians, researchers and the generally curious. It is the medals of those who were present at Maiwand that command the highest price among collectors of Afghan War awards, and the campaign has Maiwand as its most public face thanks to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who placed Doctor Watson on the battlefield on the first page of the first Sherlock Holmes adventure, A Study in Scarlet. For wargamers looking to re-enact the period, it provides the most fascination, endless debate, and countless 'what if...' scenarios played out on tabletop deserts. The recent popularity of Victorian history and genealogy has seen more and more people learn about the Second Anglo-Afghan War for the first time. A number go on to discover it was their ancestor who stood steady for as long as they could under the hot fire of the Afghan 'That Day' in July 1880, that it was their ancestor who fought his way out of hell, through the gardens of Khig and the never-ending, thirst inducing retreat back to Kandahar. Or perhaps they discover it was their ancestor who was one of the many who perished in the blazing heat of battle, in the middle of nowhere, 3,500 miles from home, their shallow grave in the dusty landscape becoming forever a little piece of England (or, come to that, India). Tuesday 27 July 1880 was the British nightmare, an Afghan lesson that has been learned, but also forgotten. In a public park in Reading stands a lion, always ready to remind us of those whose bones still lie in the Helmand Valley, and of the story that is Maiwand. |

All original content on this site is © Garen Ewing 2025, unless otherwise stated.

Original images from my own collection and data on this site should not be used without prior permission - thank you.

See about this site for more details.